Understand Science

Learn about Nutrition

Is Fiber Important?

We explore the importance of fiber for health using historical and current data, interactive data visualizations, and many scientific insights.

Author:

Elena Shekhova

Date:

We are a small team of nerds, who invest hundreds of hours each month to 'bake' LumiPie. We remain independent, without running ads or affiliating with external organizations. This project is entirely self-funded. That is why your support is very important to help us continue delivering high-quality scientific content.

Fiber Theory

There are different types of superheroes. But it is quite remarkable that scientists found a way to establish their place among Batman and Superman.

I introduce you to Denis Burkitt, The Fibre Man.

Over 50 years ago, he proposed that a lack of dietary fiber could lead to various health problems and even suggested the mechanism behind it.

Let us dive deep into his observations and hypotheses and align them with the scientific evidence we have accumulated so far.

The Beginning

Denis Burkitt was a British surgeon who moved to Africa during World War II, where he worked for 20 years in different countries including Kenya, Somaliland, and Uganda.

He was particularly good at observing patterns of diseases. After returning to Britain in 1964, he compared disease rates between different regions of the world.

One of his key observations was that colorectal cancer was frequently diagnosed in Western countries but almost unheard of in Africa (1).

Looking into these geographic patterns, Denis and other researchers tried to find a possible explanation. One idea was that differences in lifestyle played a major role (2).

Burkitt proposed that diets could explain why some disorders such as colorectal cancer, diabetes, and heart disease were more common in wealthy countries. He knew that people in Africa primarily ate unprocessed or minimally processed plant-based foods. While the typical diets in high-income countries were different.

Western diets were often low in fiber, and this, as Denis proposed, could explain the higher rates of colorectal cancer.

📝 What is fiber? Fiber is a component of plant-based foods like vegetables, fruits, legumes, and whole grains. Dietary fiber includes a diverse range of carbohydrates that cannot be broken down by enzymes in the human small intestine (3). While humans themselves are unable to degrade fiber, certain bacteria in the colon can do this. These bacteria break fiber down and transform it into smaller molecules (metabolites), such as short-chain fatty acids, which can, in turn, be absorbed by the human body. Fiber-derived metabolites can positively affect gut function and immunity, although the exact mechanisms are still under investigation.

Fiber & Cancer

Denis’s primary theory about the importance of dietary fiber began to develop from noticing that diets in wealthier countries were low in fiber, while rates of colorectal cancer were high.

We have to remember that these observations were made more than half a century ago may not hold true today.

To have a better picture of what is going on now, we will try to answer these questions:

- Do people in wealthy countries eat low amounts of fiber?

- Are they more likely to develop colorectal cancer than those living in other regions?

Fiber Gap

Today we have several databases that give us information about diets from different parts of the world. These databases help us see how much various nutrients, including fiber, people typically consume.

These databases are not completely precise but still very useful.

They are generated using data from dietary surveys, food questionnaires, interviews, or food supply records. From that data, researches can further roughly calculate the amount of nutrients in the foods people eat. These estimates are not always exact. One reason can be that people may forget what they ate when filling out surveys. However, these databases are still important and helpful for understanding global dietary habits.

Now we will explore how much dietary fiber people eat across the world using the Global Dietary Database.

We can see that fiber consumption is higher on average in Africa. In many African countries, people consume more than 30 g of fiber per day, while only a few countries in the Americas and Europe reach that level of intake.

The recommended daily amount of fiber for optimal health is at least 25 g (4). When we calculate an average daily fiber intake per capita in each region, only Africa displays average consumption above 25 g.

Overall, we can conclude that, as Denis and others noted 50 years ago, fiber intake does vary geographically, and it is lower in the Western countries than in Africa.

Wealth & Cancer

The lack of fiber in Western diets is not surprising. It is well documented that technological advances and economic growth are associated with a high degree of food processing such as grain refining (5). One example is wheat. When wheat is milled to produce white flour, it loses about 75% of its fiber (6). This means that typical Western diet products made from white refined flour like bread, pasta, and baked goods, deliver little fiber and can contribute to its deficiency.

But does this mean that the wealth of Western countries can be linked to certain diseases? Was Denis right in connecting economic growth with colorectal cancer?

We can answer these questions by checking if GDP (Gross Domestic Product) per capita, an indicator of a country’s economy, coincides with the recorded number of colorectal cancer cases.

For this, we’ll use age-standardized cancer incidence data from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation collected in 2016.

As you can see, wealthier countries tend to have more cancer cases.

However, even though we know that fiber consumption is lower in richer countries, we cannot say for sure that the lack of fiber is the reason for higher cancer rates there.

Why?

Because besides diet, many other factors could explain the higher cancer incidence in Western countries. Body weight, smoking, alcohol use, and physical activity levels also affect cancer risks (7).

That is why we better rely on epidemiological studies, which collect data in a structured way. In these studies, scientists examine how much fiber people eat and whether they get cancer over time.

Epidemiological studies help identify what factors change the risks of getting health problems.

In epidemiological studies, researchers record participant characteristics like weight, alcohol use, and smoking. These details are taken into account during analysis. This helps to determine whether changes in cancer rates are linked specifically to fiber intake, while minimizing the influence of other participant characteristics.

Cancer Risks

In a large meta-analysis that combined data from 22 epidemiological studies involving 22,920 participants (8), it was found that higher fiber intake is likely associated with a 16% reduction in the risk of developing colorectal cancer.

Let us break down what this 16% risk reduction means.

Taking the USA as an example: According to Cancer Statistics, 4 out of 100 people will develop colorectal cancer over their lifetime. If we imagine convincing everyone to eat fiber-rich foods, this number would decrease by 16%. So, instead of 4 in 100, about 3 in 100 people would develop colorectal cancer.

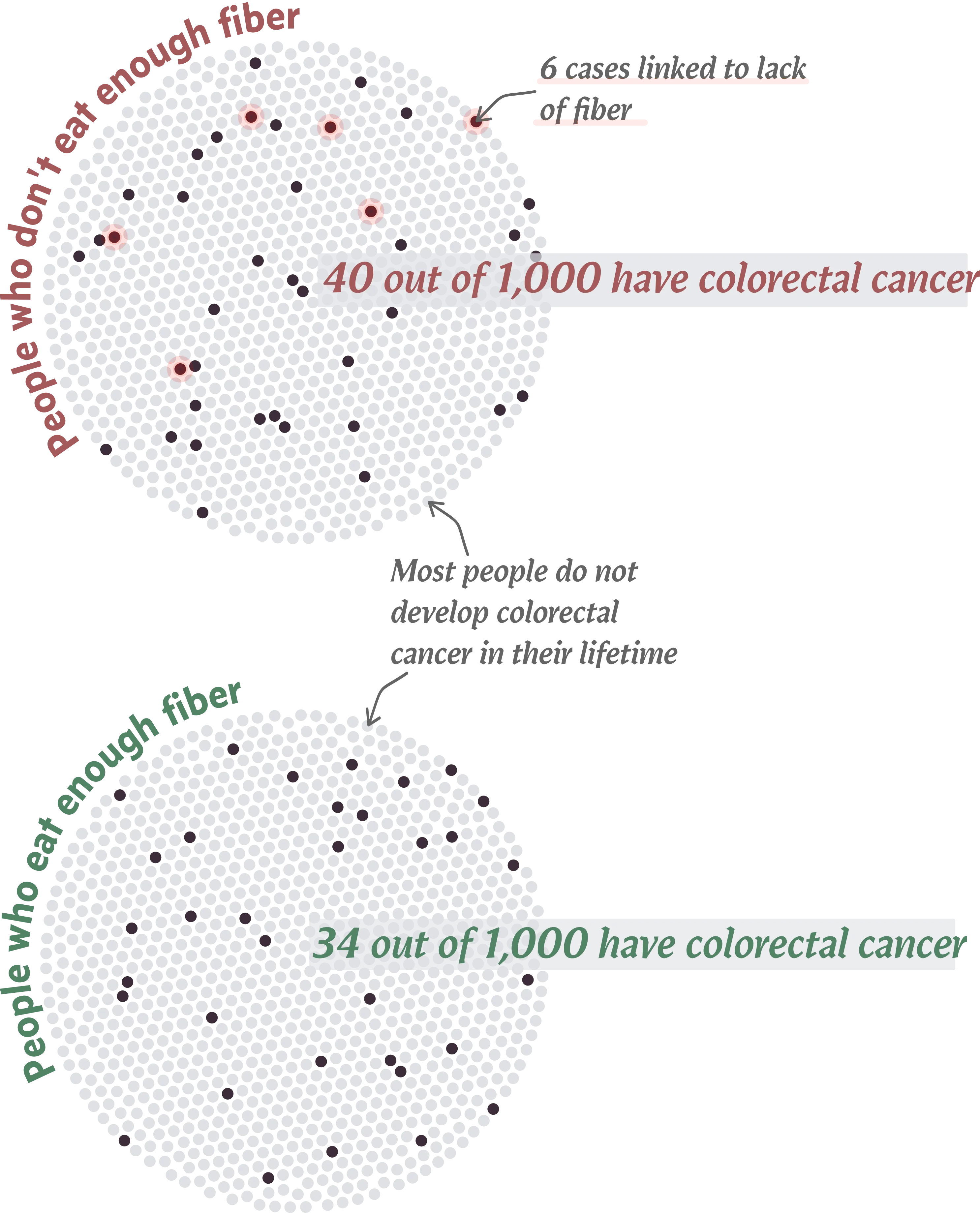

To be more precise, let’s imagine 1,000 people either eating enough fiber or not and visualize their risks:

The chart nicely shows that adequate fiber intake (above 25 g) can help prevent colorectal cancer in 6 out of every 1,000 people.

Unfortunately, we can not prevent all colorectal cancer cases with more fiber.

This is because there can be multiple reasons why people get cancer.

Talking only about diet, various dietary habits can increase or decrease the number of expected cancer cases in a population. For instance, similarly to increased fiber intake, reduced alcohol consumption and red meat can also help lower colorectal cancer rates (9).

Taking geographical and epidemiological evidence together, we can conclude that the lack of dietary fiber in Western diets may, in part, contribute to colorectal cancer.

Potential Impact

By now, we have accumulated clear evidence that many countries could see health improvements from fiber-rich diets.

We also wanted to estimate specifically how many people in the world would benefit from the positive health effects of fiber. For this, we refered to the Global Dietary Database, and to the World Bank Group to fetch population size of each country.

Based on data from 2018, approximately 4.8 billion people consume less than the recommended 25 g. The number is likely higher today.

This simply means that fiber-rich diets have the potential to prevent colorectal cancer in millions of people.

Fiber Benefits

Denis’s theory why fiber-rich diets are beneficial included the following points:

- Adequate fiber is required for optimal bowel activity, including stool formation and its transit through the digestive tract. Fiber helps to ‘shape’ the stool and pass it quickly, preventing potentially harmful substances from being absorbed.

- Fiber supports healthy microbiota where good bacteria thrive. If bad bacteria are more abundant, they may degrade bile acids (compounds produced by the body to digest fats) into potentially carcinogenic substances. Fiber helps to prevent bile acid degradation.

Let us look into his points closer and try to see if we have evidence to support them.

Stool Matters

Denis believed that fiber is essential for normal bowel habits and overall health.

One of his famous quotes is: “Societies that eat unrefined foods produce large stools and build small hospitals; societies that eat fiber-depleted foods produce small stools and build large hospitals.”

This theory came from the study results showing that, with more fiber, people tend to visit the restroom more often and have larger stools (1).

Currently, researchers still debate whether the frequency of bowel movements impacts cancer risks. However, one systematic review summarized existing data and revealed that there is no link between constipation and cancer risk (10). This means that infrequent bowel movements do not necessarily increase colorectal cancer risks.

Now, let us assess whether stool size matters.

We found no significant debate about this part of the theory. Several studies, mainly from Scandinavia, confirmed the importance of 24-hour stool weight: people consuming more fiber had larger stools and lower risks of colorectal cancer (11,12).

Denis was right — size does matter! He also suggested a mechanism behind this phenomenon: fiber makes stools bulkier, which dilutes ingested or newly formed carcinogens, reducing their absorption into the body.

Fiber & Gut Bugs

Denis was also convinced that in addition to affecting bowel habits, dietary fiber played an important role in shaping normal gut microbiota. Gut microbiota is all those bugs (bacteria, fungi, viruses) living in the digestive tract.

His theory linking fiber, gut microbiota, and colon cancer was influenced by a study conducted by Aries and colleagues in the 1960s (13). In that study, people from Britain, who ate little fiber, had very different microbiota than people in Uganda with fiber-rich diets.

By now, scientists have confirmed that dietary fiber has a great impact on bugs in the gut. Fiber increases microbiota diversity and prevents the growth of potentially harmful bacteria (14–16).

By now, we also have some clues about which specific bacteria may be associated with cancer.

Despite access to advanced technology, it remains hard to establish a clear link between the presence of certain bacteria in the gut and the likelihood of developing diseases like colon cancer. However, many studies suggest that Fusobacteria is one of the gut inhabitants associated with cancer (17,18). There are other potential suspects too. Hopefully, in the future, this information may eventually be used for diagnostic purposes (19).

Microbiota Superpower

Now let us try to understand why microorganisms that live in our guts are important against colon cancer.

Was Denis right in speculating that without enough fiber, bad bacteria degrade bile acids into products that can contribute to cancer?

Looking into scientific literature, it seems that things are rather complex.

It is not yet clear why exactly cancer starts and progresses. Besides fiber, other diet components, such as fats, may affect composition and activity of the microbiota, and therefore change cancer risks (20).

Many studies confirmed that fiber can be used by various beneficial bacteria in the gut, which produce new compounds with anticancer activities (21).

On the other hand, with a lack of fiber and an excess of fats, bad bacteria dominate the colon. They may indeed take bile acids, which are produced by the human body to digest fats, and transform them into cancer-promoting substances (21).

With more scientific studies, it will become easier to unravel why fiber-supported microbiota is protective against colorectal cancer.

Cause of Deficiency

By this point, we have seen significant evidence that fiber is beneficial. The logical question is: Why do we not eat enough of it?

There may be several reasons:

1. Food processing: In traditional diets, before the industrial revolution, grains (e.g., wheat, barley) and pulses (e.g., lentils, beans) were major sources of fiber (5). Now, in high-income countries, people consume these foods in low amounts or in a highly processed form.

While food processing improves safety and shelf stability, it may also result in the loss of nutrients, including fiber.

Let us take rice as an example. Most of the fiber in rice is concentrated in its outer layer. When wholegrain rice is refined (through dehusking and polishing), the outer part is removed, and with it, most of the fiber is lost (22).

2. Animal-based products: In Western diets, the majority of protein comes from animal-based products such as meat, dairy, and eggs. This means that pulses, which can provide both protein and fiber, are eaten less frequently or not eaten at all. As a result, the low intake of plant-based proteins can be linked to a lack of dietary fiber.

⏳ But more on this later. We will cover the role of animal-based products in modern diets in a separate article.

Wrapping

Historically, dietary fiber has been recognized by scientists as an important part of a healthy diet.

This was noted more than 50 years ago and continues to be true today:

- In rich countries, people do not eat enough fiber (at least 25 g per day is recommended)

- More fiber means lower risks of colorectal cancer

- Fiber makes the stool bulkier (and it is a good thing!)

- Fiber supports an optimal gut microbiota (more good bacteria, less bad ones)

Disclaimer: This article has been carefully researched and reviewed to provide accurate information. However, if you notice any errors, inaccuracies, or have questions regarding our content, please reach out to us at info@lumipie.com. We appreciate any feedback.

Methods and Sources

This article represents a compact summary of key research papers on dietary fiber, all referenced below and numbered in the main text. The databases used for creating the visualizations are cited in the main text, with corresponding links provided. These were downloaded in 2024. The data was used without any processing, except for one data point on daily fiber intake in Montenegro, which was excluded from the visualization due to a potential estimation error.

1. Burkitt DP. Epidemiology of cancer of the colon and rectum Cancer. 1971;28(1):3–13.

2. Cummings JH, Engineer A. Denis Burkitt and the origins of the dietary fibre hypothesis Nutrition Research Reviews. 2018 Jun;31(1):1–15.

3. Gill SK, Rossi M, Bajka B, Whelan K. Dietary fibre in gastrointestinal health and disease Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2021 Feb;18(2):101–16.

4. McKeown NM, Fahey GC, Slavin J, van der Kamp JW. Fibre intake for optimal health: How can healthcare professionals support people to reach dietary recommendations? The BMJ. 2022 Jul;378:e054370.

5. Huebbe P, Rimbach G. Historical Reflection of Food Processing and the Role of Legumes as Part of a Healthy Balanced Diet Foods. 2020 Aug;9(8):1056.

6. Mikušová L, Šturdík E, Holubková A. Whole grain cereal food in prevention of obesity Acta Chimica Slovaca. 2011;

7. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2021;71(3):209–49.

8. Reynolds A, Mann J, Cummings J, Winter N, Mete E, Morenga LT. Carbohydrate quality and human health: A series of systematic reviews and meta-analyses The Lancet. 2019 Feb;393(10170):434–45.

9. Veettil SK, Wong TY, Loo YS, Playdon MC, Lai NM, Giovannucci EL, et al. Role of Diet in Colorectal Cancer Incidence: Umbrella Review of Meta-analyses of Prospective Observational Studies JAMA Network Open. 2021 Feb;4(2):e2037341.

10. Power AM, Talley NJ, Ford AC. Association between constipation and colorectal cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2013 Jun;108(6):894–903; quiz 904.

11. Cummings JH, Branch WJ, Bjerrum L, Paerregaard A, Helms P, Burton R. Colon cancer and large bowel function in Denmark and Finland Nutrition and Cancer. 1982;4(1):61–6.

12. MacLennan R, Jensen OM, Mosbech J, Vuori H. Diet, transit time, stool weight, and colon cancer in two Scandinavian populations The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1978 Oct;31(10 Suppl):S239–42.

13. Aries V, Crowther JS, Drasar BS, Hill MJ, Williams RE. Bacteria and the aetiology of cancer of the large bowel. Gut. 1969 May;10(5):334–5.

14. De Filippo C, Cavalieri D, Di Paola M, Ramazzotti M, Poullet JB, Massart S, et al. Impact of diet in shaping gut microbiota revealed by a comparative study in children from Europe and rural Africa Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010 Aug;107(33):14691–6.

15. Katsidzira L, Ocvirk S, Wilson A, Li J, Mahachi CB, Soni D, et al. Differences in Fecal Gut Microbiota, Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Bile Acids Link Colorectal Cancer Risk to Dietary Changes Associated with Urbanization Among Zimbabweans Nutrition and Cancer. 2019;71(8):1313–24.

16. Ramaboli MC, Ocvirk S, Khan Mirzaei M, Eberhart BL, Valdivia-Garcia M, Metwaly A, et al. Diet changes due to urbanization in South Africa are linked to microbiome and metabolome signatures of Westernization and colorectal cancer Nature Communications. 2024 Apr;15(1):3379.

17. Tabowei G, Gaddipati GN, Mukhtar M, Alzubaidee MJ, Dwarampudi RS, Mathew S, et al. Microbiota Dysbiosis a Cause of Colorectal Cancer or Not? A Systematic Review Cureus. 14(10):e30893.

18. M ZR, Ss M, H B, H W, A BM, P M, et al. A distinct Fusobacterium nucleatum clade dominates the colorectal cancer niche Nature. 2024 Apr;628(8007).

19. Qu R, Zhang Y, Ma Y, Zhou X, Sun L, Jiang C, et al. Role of the Gut Microbiota and Its Metabolites in Tumorigenesis or Development of Colorectal Cancer Advanced Science. 2023 Jun;10(23):2205563.

20. Ocvirk S, O’Keefe SJD. Dietary fat, bile acid metabolism and colorectal cancer Seminars in Cancer Biology. 2021 Aug;73:347–55.

21. Zeng H, Umar S, Rust B, Lazarova D, Bordonaro M. Secondary Bile Acids and Short Chain Fatty Acids in the Colon: A Focus on Colonic Microbiome, Cell Proliferation, Inflammation, and Cancer International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2019 Jan;20(5):1214.

22. Oghbaei M, Prakash J. Effect of primary processing of cereals and legumes on its nutritional quality: A comprehensive review Cogent Food & Agriculture. 2016 Dec;2(1):1136015.